अनभूले पैठणी येवला

. No.

|

Common Name

|

Scientific Name

|

Part Used

|

Colour Obtained

|

1

|

Phanas

|

Atrocarpus heterophyllus

|

Bark

|

Yellow

|

2

|

Gulmohar

|

Delonix Regia

|

Flower

|

Olive Green

|

3

|

Sagwan

|

Tectona Grandis

|

Leaves

|

Yellow

|

4

|

Babool

|

Acacia nilotica

|

Leaves, Bark

|

Yellow and Brown

|

5

|

Kamod/ Nilofer

|

Nymphaea alba

|

Rhizomes

|

Blue

|

6

|

Awala

|

Emblica officinalis

|

Bark, Fruit

|

Grey

|

7

|

Boracha zhad

|

Ziziphus mauritiana

|

Leaf

|

Pink

|

8

|

Shevgyacha zhad

|

Moringa pterygosperma

|

Leaf

|

Yellow

|

9

|

Chinchecha zhad

|

Tamarindus indica

|

Leaves, Seeds

|

Brown

|

10

|

Red Sandalwood

|

Pterocarpus santalinus

|

Wood

|

Red

|

11

|

Kardai cha Phool

|

Carthamus tinctorius

|

Flower

|

Orange-red

|

12

|

Halad

|

Curcuma longa

|

Rhizome

|

Yellow

|

13

|

Neel

|

Indigofera tinctoria

|

Leaf

|

Blue/ Indigo

|

14

|

Mehendi

|

Lawsonia inermis

|

Leaf

|

Red

|

15

|

Amba

|

Mangifera indica

|

Bark and Fruit

|

Yellow

|

16

|

Bakul

|

Mimusops elengi

|

Bark

|

Brown

|

17

|

Parijat

|

Nyctanthes arbor-tristis

|

Flower

|

Bright orange

|

18

|

Jhendu

|

Tagetes erecta

|

Flower

|

Yellow

|

19

|

Ala

|

Zingiber officinale

|

Rhizome

|

Brown

|

20

|

Jhambul

|

Syzygium cumini

|

Fruit

|

Purple/black

|

21

|

Kusumb

|

Schleichera oleosa

|

Fruit

|

Red

|

Some of the Paithani colours evolved through these organic dyes are: jambhuli (purple), morpankhi (peacock blue), neelambar (bright blue), motiya (peach), falsa (magenta), kusumbi (purple-red), kanchi hirva (bottle green), pasila (red-green), gujri (grey), mirani (deep red), banosi/dalimbi (deep red), gangavarni (indigo blue), chanderi (silver grey), soneri (golden yellow) as well as typical colours such as lal (red), pivla (yellow), shendri (saffron) (Prerna 2012).

In the present scenario, the dyes used are chemical dyes which give a vast range of colour options. The silk is pre-dyed and obtained from Bangalore Silk Board. Orders are given for required colours. The avaibility of chemical dyes has enabled a larger range of colours and shades.

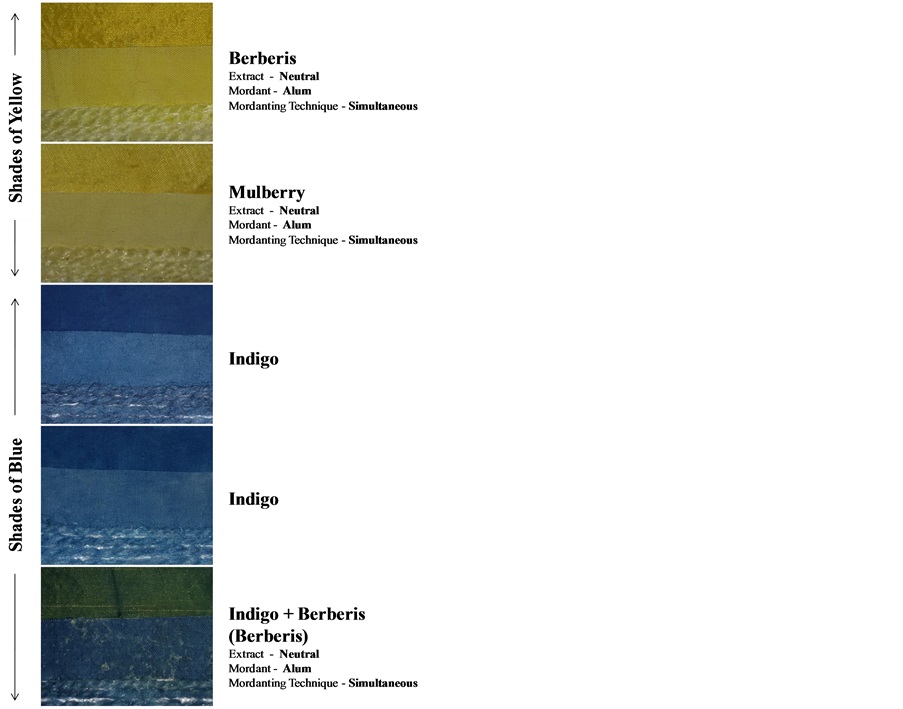

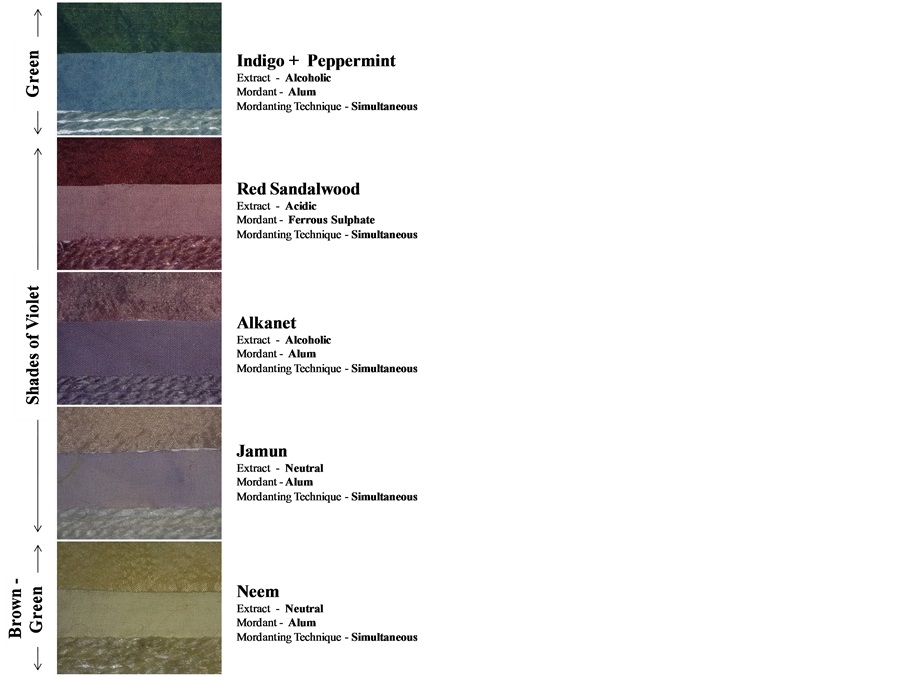

The range of colours obtained by combining various mordant and natural dyes is given below (Arora 2017).

Figure 4. Range of dyes in silk

Figure 5. Organic dyes on silk (top)

Figure 6. Organic dyes on silk (top)

Figure 7. Organic dyes on silk (top)

Figure 8. Organic dyes on silk (top)

Preparation of weaving

The preparation for weaving the Paithani saree itself takes about four to five days, from preparation of the tana and the bana to preparing the loom.

j

The tana (warp) is first prepared by stretching and separating the silk threads. It is stretched multiple times by wrapping around a spindle to smoothen out kinks and detangle the thread.

It is then wrapped around the drum of the loom which is known as the dhol. It is ensured that the tana is tightly wrapped around the dhol to maintain tension. Loosening of the tana causes unequal weaving and warping of the saree.

Figure 11. Attaching to the ata

A beam called the ata is then attached to the rear of the loom and the tana sorted into bundles of ninety threads. The ata has sixteen reels spaced evenly on it. The tana has seventeen and a half bundles of ninety threads.

Figure 12. Jodni by hand

The threads in the bundles are then joined individually by twisting through the heddles. This process is called jodni. It is a time-consuming process and takes 12 to 18 hours to finish. The process involves taking each thread and joining them alternatively over and under a bar of the loom.

Figure 13. Thape and Phalka

Figure 14. Preparing the bana

The bana (weft) is prepared on the thape, which are a set of three stone pedestals. The thape are three wooden rods on stone bases, one of which has grooves to hold the phalka (a large cage made of string and bamboo). The ready bana is then shifted to the tansal. The weft is generally three or five ply and is prepared by winding on the thape multiple times.

After creating the three-ply weft on the tansal, it is stretched on the yantra (spinning wheel), and wound around kandya(bobbins). The kandya are usually made of pine wood and tapered at both the ends.

The loom is generally made of teak wood as it is more durable and less prone to warping or decay. However, today, due to limitations, only the warp beam, cloth roller and beater are made of teak wood as these need to be durable to prevent any defect in the cloth.

The parts of the loom are:

Ata - back beam with seventeen divisions

Dhol - warping beam/ warp roller

Hatya - beater

Dhota - shuttle

Pavdya - treadles

Phani - reed heddles

Tulai - cloth roller

Kandya - bobbin

After the preparation of the warp and the weft, the saree is ready to be started.

The weaving process

The first element of the saree to be woven is the pallu or the padar. The padar is woven in zari weft over a silk warp. The zari was traditionally silver with a wash of gold but today has a base of bronze. The padar contains the distinctive motifs of the Paithani such as the mor, bangdi mor, kamal, asawali and akruti. The padar is one of the most intricate and time-consuming parts of the Paithani to be woven and takes anywhere from two weeks to two months to weave depending on its length, level of detail and intricacies of the motifs.

The motifs are in silk bana over a base of gold zari and while weaving, the weaver counts the number of threads by feeling them with his fingertips. This is a skill acquired over years of practice. The simplest motifs are the buttis and the tota while the most difficult to weave is the bangdi mor. The padar will generally have a central element such as the kunda mor(peacock on a vase), phulzhad (tree with flowers or peacocks), padmakamal (lotuses) or bangdi mor (peacocks in a circle). These central elements will be banded in long narrow borders of tota maina, vel, koiri motifs or bands of vertical dashed lines to enhance the padar.

Figure 17. Implements for weaving

The body of the Paithani is the next part. The body is defined by a border on its edge. If the body of the saree is plain, a throw shuttle is used, however, if buttis are present, then each butti is handwoven in zari.

Figure 18. Weaving the body of the saree

The saree might have a total of 200 to 300 buttis woven. A complete Paithani will have all buttis handwoven which is a slow and time-consuming process. The buttis also come in different motifs such as peacocks, flowers, petals, paisa and parinda.

The designs of the Paithani are preset and each designer adds elements as he weaves. The weaver can make designs or use typical traditional patterns. However, the count of threads while weaving remains the same always. In a day’s work, the weaver weaves two inches of padar and five to six inches of body on an average. Each saree, hence takes a minimum of three months to weave if it’s completely handwoven. A saree with a thick 18-inch border and 36-inch padar will take a year to weave. While weaving, the tana is checked for equal tension by feeling it with fingers. If found to be unequal, the relevant reel on the ata is tightened and the tana is then wet with water to increase tension. Unequal tana will cause snarls in the fabric of the saree. After every 3 to 4 inches, the zari is polished with a mixture of gum and water to stiffen and preserve it. This polishes the zari, seals any loose threads and stiffens the border. Sticky substances such as jaggery, methi or gum is used in the mixture. These substances do not cause any deposits or marks in the zari. The zari used is either of copper with gold or silver thread coated with gold. The tana is of silk, however the bana is of zari. This causes the zari border to have a distinctive colour. If the zari is of silver, the zari border and padar will have a reddish tinge, however, if the zari is bronze based, the zari will be a bright golden yellow in colour. The saree is carefully unwrapped from the cloth roller (tulai), cleaned and folded.

The colours of the saree are obtained by combining different colours of tana and bana. This increases the spectrum of colours of the Paithani. For example, a red tana and a blue bana will give a shade of purple, while a tana of black silk and a bana of green will give a shade of dark green Paithani. Certain shades of colours will give a dhuup chaon (dual tone) effect to the saree with changing colour. This combination enables creating a variety of colours of Paithanis based on a limited number of colours in the tana and bana. If the saree is of a single colour warp and weft it is known as daryai. If the saree is of two different coloured warp and wefts it is known as dhoop chaon. If multiple colours are used in warp and weft it is known as par-i-taus, and if chequered it is known as charkhani (Morwanchikar 1993).

Vernacular terms of weaving

The weavers have a vernacular name for every process and part of weaving the Paithani, however, due to decrease in the weavers’ community, lessening of awareness of the techniques of weaving and lack of written documentation, some of the terms are lost today. Even then, the most commonly used terms are mentioned below. They include terms for boiling of silk, preparing the tana and bana, and nomenclature of the parts of the loom:

Ukalap - sorting silk thread based on quality and thickness

Ukhar - bleaching of silk in boiling solution of sodium carbonate or papar khar or chuna

Tana - warp

Bana - weft

Phalka - cage of bamboo and string

Asari - conical reel

Yantra - spinning wheel

Khandki - bobbins made of reed

Sacha - bobbin frame

Rahat/dhota - throwing spool

Turai - cloth beam

Hatya – reed frame

Phani - comb for weaving

Ata - warping beam

The weavers of Paithan

Historically, Paithan has always been centered around the weaving industry. Every household in Paithan was linked with weaving and ancillary activities such as dyeing the silk, winding the zari or even selling the silk sarees. A majority of the population of Paithan was involved in weaving the sarees with the Koshtis, Salis and the Momin communities consisting of the larger part of the demography. Today, only a few weaving families remain involved in the traditional occupation of weaving. A few such distinguished families are also recipients of the National Award for weaving.

Learning the art of Paithani weaving was a long and arduous process with the apprentice being introduced to the task at the young age of twelve or fourteen. The first task given to the apprentice was to sort the silk thread and prepare the bobbins. As he grew adept in handling the thread, he was taught the art of weaving a plain silk cloth by using a shuttle and taught how to operate the loom. When the master weaver felt that the apprentice was ready to learn the motifs, he was given the task of weaving simpler motifs and buttis such as the tota and the sunflower. The apprentice had to practice multiple times till he could weave perfect motifs. This could take a fast learner six to eight months to achieve. Then he slowly graduated on to weaving the body for the saree with its border. More complicated motifs such as the peacock and the lotus were then introduced to him. The last motif generally taught was the bangdi mor as it is the most complex. An apprentice would continue in his tutelage for two to four years before he could be given an entire saree to be woven.

The structure of the weavers is such that a master weaver generally has four to eight looms in his house and has an equal number of apprentices involved at varying stages of capability. Each master weaver in turn was patronised by a family of sahukars who took care of the orders. They provided materials, the investment required and ensured that the Paithanis are marketed and sold in other cities. The weavers from Paithan were often invited under royal patronage to settle in various places. The king of Gujarat, Siddharaja Solanki, invaded Paithan and took the craft to Gujarat in the 12th century CE by extending invitations to the weavers to settle in Yeola and parts of Gujarat.

Paithani received royal patronage under Aurangzeb, the Marathas and Peshwas, as well as the Nizams. The high cost of materials as well as the time and effort required for weaving and the high selling price caused its decline in the 20th century. Today, three to four families remain who can state an unbroken line of weaving back to four or five generations. The Maharashtra government rejuvenated the art by training women in the Paithani Kala Kendra. Today some 200 women are trained in this traditional art of weaving.

Not just the weavers but a variety of different communities are involved in the creation of the saree:

1. Dyeing - Bhavsar community

2. Gold and silver work - Sonar community

3. Zari - Pavtekar and Chapade communities

4. Separating (Winding silk from dyed bundle onto loom) - Women from Sali, Koshti and Momin communities

5. Weaving - Sali, Koshti and Momin communities

Paithani weaving has influenced the town and settlement of Paithan with the various communities living together and forming distinct smaller settlement areas such as Saliwada or Rangarrahatti. The names of the suburbs such as Rangarhatti, Chapade-gali, Taru-gali, Pavata, are more than suggestive of this. The area of ‘Rangarhatti’ is named after the inhabitants who did the bleaching and dyeing work. The area of Taru-gali, after the taru who transferred gold-silver bars into threads. Jar-galli was a place where the gold threads were wound with silk. There is yet another place called Pavata where big machines for making gold and silver strips were fixed (Ministry of Textiles GoI 2008).

The motifs used in Paithani also influenced the architecture of the Wadas with similar motifs being used in brackets and arches. Houses of the traders or sahukars, for example, display special rooms used for storage of raw materials and finished silk cloth. Such rooms are wooden enclosures above the entrance with proper ventilation and moisture controlling measures.

No comments:

Post a Comment